Understanding the term service vehicle is essential for local private car owners, used car buyers and sellers, and small business fleet operators. This term describes vehicles that are designed not just for personal commuting but to deliver essential services across various sectors. As urbanization increases, the role of service vehicles becomes even more vital. This article will delve into their definition and purpose, explore the various types of service vehicles, and examine their profound impact on society, emphasizing how they support public services and infrastructure. By the end, you’ll gain a comprehensive understanding of what service vehicles mean and their significance in everyday life.

Defining Service Vehicles: Purpose, Legal Meaning, and Day-to-Day Roles

A precise understanding of what a service vehicle means starts with the idea that its primary purpose is to deliver a specific service rather than to carry passengers or goods in the ordinary sense. This definition is practical and legal. In regulatory texts, a service vehicle is often described as a motor vehicle, including any trailer attached, that is regularly used to transport an applicator, equipment, or materials needed for a task. That simple phrasing captures three core elements: a vehicle as a platform, repeated or regular use for service work, and a cargo that supports a professional activity. The emphasis on regular use matters. A personal pickup used once to move a lawnmower does not become a service vehicle. A van fitted out with sprayers, containment cabinets, and safety gear that a pest-control technician drives daily does.

From that baseline, the concept expands into a range of public and private roles. Service vehicles act as mobile extensions of workplaces. They carry tools, parts, and personnel to the point where work must happen. In emergencies, they deliver life-saving response. In maintenance work, they bring specialized equipment to the asset that needs repair. In community services, they function as moving infrastructure—collecting waste, clearing roads, or offering on-site services like mobile clinics. This functional perspective clarifies why the term appears across so many legal, insurance, and operational documents: it describes not just a machine, but a node in a service delivery system.

Legal and regulatory contexts add detail and constraints. Where hazardous substances are involved, statutes often define service vehicles to ensure safety and traceability. Agricultural and environmental rules, for example, typically treat a vehicle as a service vehicle when it transports an applicator and pesticides. That triggers requirements for secure storage, labeling, spill kits, training for handlers, and often specific registration or recordkeeping procedures. Regulations target risk: the combination of mobility and hazardous cargo means spills or improper use can affect public health and ecosystems. Accordingly, regulators focus on containment, ventilation, and the segregation of incompatible materials, as well as training and documentation to prove safe handling.

Beyond hazardous materials, classification affects insurance, taxation, and compliance. Insurers view service vehicles differently from passenger cars. Their use introduces different liabilities: equipment can cause injury in a crash, a misplaced tool can damage property, and specialized cargo can create unique risks. Insurers ask about upfit details—the shelving, racks, tanks, lifts—that alter a vehicle’s center of gravity and crash profile. Premiums, deductibles, and policy terms may follow. Tax authorities, too, distinguish business-use vehicles. A service vehicle may qualify for deductions or different depreciation schedules, reflecting its role as a capital asset rather than personal transport. Fleet managers must therefore track use carefully, keep maintenance logs, and document training to support insurance claims and tax filings.

Design and equipment reflect purpose. A service vehicle is rarely a stock model straight from a showroom. It is tailored with racks, cabinets, secure compartments, or mounted equipment. A utility truck might include a lift, hydraulic tools, and a generator. A mobile clinic will be fitted with climate control, medical refrigeration, and examination furniture. A pest-control van will contain segregated chemical storage with secondary containment and eyewash stations. These design choices focus on efficiency, safety, and regulatory compliance. They also determine maintenance needs. Custom fittings require their own inspections and replacements, and some installations must meet electrical or pressure-vessel codes.

Operational practices follow from this equipment. Service vehicles are planned and managed to minimize downtime and risk. Route planning blends the need to reach dispersed job sites with considerations like weight limits, travel restrictions, and the availability of safe parking for loading and unloading. Response vehicles prioritize speed and predictable positioning to support emergency work. Preventive maintenance calendars are essential: a service vehicle out of service disrupts operations and imposes replacement costs. Telematics and fleet software now play a central role. They track location, engine hours, idling time, and service intervals. They also record operator behavior—speeding, harsh braking, or unauthorized use—so operators can coach safer habits.

Operator training is another defining element. Driving a vehicle is only part of the skill set. Operators must understand how to handle the specific equipment, secure loads properly, and follow safety procedures for the materials they carry. For vehicles that transport hazardous substances, training is often legally mandated. Workers must know emergency procedures, containment measures, and the correct use of personal protective equipment. Simple errors—failing to close a drum, leaving a valve loose, or parking on unstable ground while using a boom—can cause costly incidents. Clear checklists and routine inspections reduce these risks and are usually part of company policy.

Signage and livery serve both practical and legal functions. Marking a vehicle as belonging to a utility or a public service helps with identification on worksites, gives authority during traffic direction tasks, and supports theft deterrence. Reflective markings, amber lights, and sirens for authorized vehicles improve safety during roadside operations. For vehicles carrying regulated substances, placards or labels communicate hazards to first responders. The markings must often meet standards, which specify size, placement, and content. These visual cues become part of the broader safety system.

The distinction between a service vehicle and other commercial vehicles is often subtle but important. A delivery truck transports goods from point A to point B as its central role. A service vehicle, by contrast, carries tools and personnel to perform a task on location. That difference influences design: a delivery truck prioritizes cargo volume and packing efficiency. A service vehicle values access to tools, secure storage for small parts, and built-in workstations. The contrast also affects insurance underwriting and regulatory treatment. Two vehicles may look similar externally yet fall under different rules based on how they are used.

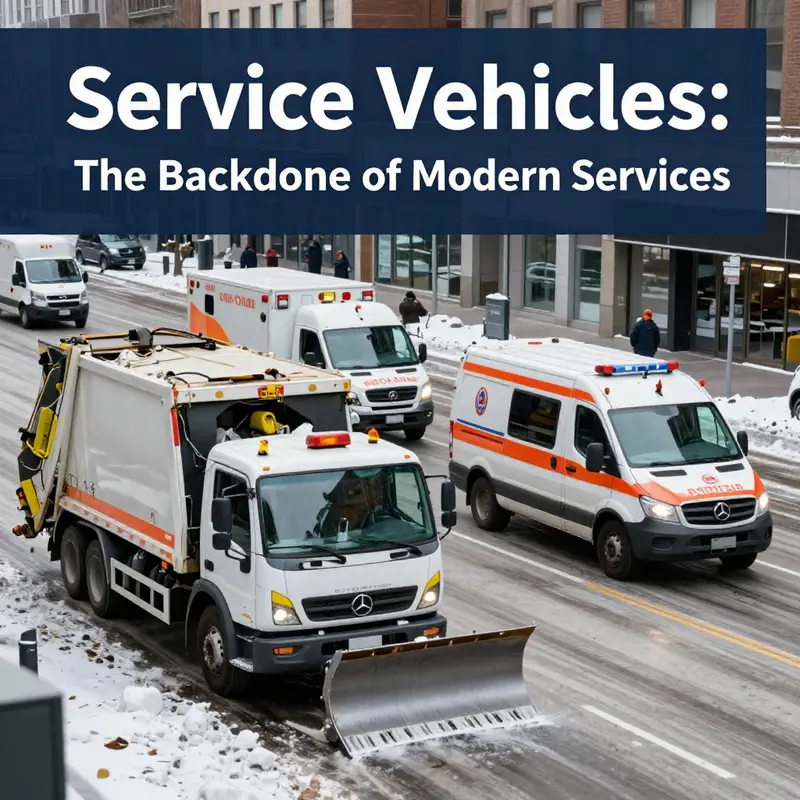

Municipal and utility fleets illustrate scale and variety. Cities operate garbage trucks, street sweepers, and snowplows as service vehicles. Each serves a public function and has unique operating windows—overnight sweeping, winter salting, daytime refuse collection. Utility companies run fleets of service trucks that include bucket lifts, cable reels, and diagnostic instruments. These vehicles support critical infrastructure and are often prioritized for rapid response during outages. Their management emphasizes readiness: spare parts, technician schedules, and staging plans for high-demand periods such as storms.

Private-sector service vehicles also cover diverse needs. Mobile service units deliver hands-on business models directly to customers: food trucks, mobile pet groomers, or on-site vehicle repair vans. These vehicles combine commerce and service delivery. They must meet both vehicle safety rules and the regulations that govern the service performed on board—food safety for kitchens, sanitary controls for clinics, and waste disposal rules for mobile repair shops. This mixed regulatory environment means operators must manage dual compliance: roadworthiness and sector-specific permits.

Environmental and community impacts shape modern approaches. Service vehicles often interact with public spaces and sensitive environments. Runoff from a vehicle washing operation, fumes from idling engines, or accidental chemical release can harm communities. As a result, many organizations adopt greener practices: low-idle policies, use of cleaner fuels, and electrification of suitable vehicle types. Electrified vans and trucks reduce local emissions and noise, improving acceptance in urban service delivery. The change requires infrastructure investments—charging stations, upgraded electrical systems—and a rethink of route planning to match range and charging needs.

Recordkeeping and documentation are core compliance tools. For vehicles carrying regulated materials, logs track the amount transported, the destinations, the personnel involved, and any incidents. Maintenance records prove inspections occurred and repairs met standards. Training logs demonstrate that operators completed required courses. These records reduce liability, support audits, and help refine operations by identifying recurring issues. Digital systems simplify these tasks, capturing data automatically and providing searchable archives for regulators or insurers.

Safety cultures matter more than any checklist. A well-structured safety culture encourages reporting of near-misses, supports regular refresher training, and rewards careful operation. The physical design of a vehicle—non-slip steps, secure handholds, and organized storage—reduces fatigue and errors. Organizational practices—clear handover notes for shift changes, mandatory pre-trip inspections, and limits on solo work in hazardous conditions—further reduce risk. When safety becomes part of daily work, service vehicles stop being liabilities and become reliable assets.

Cost management ties all of these elements together. Purchasing a vehicle is the first cost. Outfitting it to meet service needs adds to the capital expense. Insurance, fuel, maintenance, and compliance make up ongoing costs. Efficient route planning and preventive maintenance reduce total cost of ownership. Decisions about leasing versus ownership hinge on usage patterns and tax treatments. For first-time operators, basic maintenance advice can prevent early problems; resources such as truck maintenance tips for first-time owners provide practical guidance to keep vehicles roadworthy and reliable.

Finally, the meaning of “service vehicle” evolves as technology and business models change. Telematics and automation enable smarter scheduling and predictive maintenance. Electrification alters fueling and maintenance regimes. Mobile services expand into new niches, challenging cities to update parking and permit frameworks. Yet the core idea remains: a service vehicle exists to perform work where it is most needed. It is a tool, a workplace, and often a regulated environment. Understanding its definition clarifies obligations and unlocks the operational choices that make service delivery safe, efficient, and sustainable.

For readers who want to review legal definitions used in contracts or regulatory language, one helpful reference is Law Insider’s entry on the term. It provides a contractual perspective that highlights how precise language affects responsibilities and liability: https://lawinsider.com/dictionary/service_vehicle

What a Service Vehicle Really Means: Vehicles as Mobile Worksites, Public Utilities, and Engines of Service

A service vehicle is not simply a mode of transport. It is a deliberate fusion of mobility and function, a rolling extension of a team’s capability, and in many contexts a decisive lever for rapid response, reliable maintenance, and ongoing public service. In everyday life we rely on these vehicles whenever a job must be done away from a fixed base. They carry not only people but a carefully chosen array of tools, parts, equipment, and safety gear that allows work to begin the moment the vehicle arrives at a location. This is the core idea behind the term service vehicle: a vehicle whose primary purpose is to deliver a service, not merely to ferry someone from point A to point B. The service mission can range from lifesaving work to routine upkeep, and the vehicle itself is often configured to support that mission with specialized features that ordinary passenger cars do not require. The result is a kind of moving workshop whose design, equipment, and operating logic are oriented toward on-site problem solving and service fulfillment rather than personal transportation.

The breadth of what counts as a service vehicle becomes evident when we consider the contexts in which these machines operate. In many industries, the service vehicle is the frontline tool for reaching customers, safeguarding public infrastructure, and ensuring rapid, efficient delivery of critical services. In emergency response, the image that comes to mind is of bright, purpose-built units that convey responders, medical supplies, or firefighting gear to the scene with urgency and precision. An ambulance, a fire engine, or a police cruiser epitomizes the idea of service under pressure. Yet the same logic applies beyond urgent care and law enforcement. A maintenance technician who travels to a customer’s site with a van filled with diagnostic instruments, spare parts, and specialty tools embodies the same principle: the vehicle is the visible, operational core of the service provided, allowing expertise to be deployed directly where it is needed rather than after a trip back to a workshop or depot. In this view, service vehicles are mobile extensions of the service provider’s capacity, and their value lies in the speed, reliability, and completeness with which they can perform work in the field. The vehicle becomes an on-site workspace, a focal point for coordination, and a guarantee that the service begins at arrival, not after a delay.

The landscape of service vehicles spans several broad though overlapping categories. First, there are emergency response vehicles, which must be ready to act in critical moments. These are designed to balance speed with life-support capability and safety, carrying equipment that can stabilize situations while professionals assess the next steps. The aim is not to entertain the idea of a perfect cure on the move; it is to ensure that the moment help arrives, it is equipped to do what is necessary to protect life, reduce harm, and support the longer rescue sequence. Then there are maintenance and repair vehicles, which function as mobile workshops for tradespeople and technicians who must perform diagnostics, repairs, and installations away from a central workshop. These vehicles carry tools, spare parts, and often power sources, enabling a job to proceed from arrival to completion without requiring a return trip for materials. In many cases, a single vehicle can be adapted for multiple tasks by swapping tool kits or attaching temporary equipment storage modules, reflecting the practical reality that service demands fluctuate with season, client needs, and project scope.

Utility and municipal service vehicles illustrate another important facet. Waste collection, street cleaning, snow removal, and utility line maintenance all rely on fleets that bring specialized capacity to the public realm. In these applications, the vehicle is more than a conveyance; it is a moving platform for performing essential tasks in the public space. The vehicle’s configuration—whether it includes a lifting arm, a container, a sweeper mechanism, or a bed for securing materials—directly shapes how efficiently services can be delivered. Finally, mobile service units operate in more varied markets, from temporary clinics and food services to on-site banking or remote diagnostics. These examples underscore a recurring pattern: service vehicles are not primarily about moving people, but about delivering a service where and when it is needed, with the ability to operate at the end point as a temporary, self-contained workspace.

In everyday business operations, the legal and accounting language around service vehicles often emphasizes their role in supporting ongoing activity rather than transporting staff for commuting. A company may classify a vehicle as a service asset if its principal use is to support day-to-day operations beyond the simple transfer of personnel. This distinction matters for how a fleet is managed, how depreciation is calculated, and how the vehicle is documented for tax and compliance purposes. Within this context, there are additional specialized declarations. For instance, a business might employ courtesy vans to shuttle customers or provide temporary replacements, while delivery trucks function to move goods or equipment from supplier to client. A fleet that enables service continuity, rather than just mobility, places the vehicle at the heart of the service chain. The practical implication is clear: the design, equipment, and operational procedures of these vehicles must align with the service mission, and the total cost of ownership must reflect the vehicle’s role as a portable service platform rather than a personal conveyance. If you imagine a plumbing company, a mobile technician, or a telecom installer, the vehicle becomes part of the service proposition itself—carrying the tools, test equipment, and spare parts needed to complete work on the first site visit, reducing downtime and improving customer satisfaction.

The agricultural and chemical application sector adds another dimension to the concept. Here a service vehicle is defined as a motor vehicle, sometimes with an attached trailer, that regularly transports an applicator and their equipment or chemicals to field sites. This framing highlights how the vehicle supports specialized fieldwork that must be conducted with safety and regulatory considerations in mind. The vehicle, in this case, is more than a shuttle for people; it is a rolling base of operations that ensures the applicator can perform the task safely and efficiently in diverse locations. The attached trailer, if used, expands capacity for payloads such as tanks, pumps, or sprayers, reinforcing the idea that the vehicle’s primary identity is tied to its ability to enable and support field service delivery rather than to provide ordinary transportation alone.

The broader perspective on service vehicles emphasizes the vehicle as a mobile workshop. In many technical sectors—telecommunications, HVAC, electrical contracting, and IT support—the vehicle becomes an essential component of service infrastructure. Technicians arrive equipped to diagnose, install, repair, or upgrade systems on site, and the vehicle’s layout is deliberately organized to sustain this work. There is a logic here that people who keep essential services online are deeply familiar with: every hour of field service is maximized when the technician can retrieve the right tool from a well-organized system of drawers, racks, and compartments, when power is available to run a diagnostic device, and when spare parts can be tucked into a dedicated storage space for immediate replacement. The idea of the service vehicle as a mobile workshop captures the essence of the model: the vehicle enables work to begin the moment it arrives, embodying efficiency, readiness, and the capacity to adapt to on-site constraints. It is a practical embodiment of service in the sense that service is not a static promise; it is a performable action that is completed through the vehicle’s capacity to bring both people and solutions to the client location.

The operational implications of this concept extend beyond the individual job. Fleet managers think in terms of reliability, route planning, inventory management, and lifecycle costs. A service vehicle must be dependable, not only for the safety of the technician but for the continuity of service for customers who rely on prompt responses. Telematics and data-driven scheduling become essential tools in aligning a fleet’s capabilities with demand patterns. A mobile service operation can be optimized by aligning vehicle inventory with typical work orders, ensuring technicians do not spend unnecessary time seeking parts or tools. In some configurations, a vehicle acts as a temporary but complete workspace, with onboard generators, climate control, and power outlets that support electronic testing and calibration. In others, the emphasis is on modularity: a base vehicle with interchangeable modules to accommodate a plumbing kit one week and a wiring harness kit the next. The result is a flexible, resilient service architecture, where the vehicle is as much a strategic asset as a mode of transport.

The social and economic significance of service vehicles extends into access to services and resilience in communities. In urban settings, service fleets enable rapid response to a broad range of needs, from routine maintenance to emergency support. In rural areas, where distances to workshops are greater, the mobile capability of service fleets often represents a lifeline for critical services such as healthcare outreach, utility maintenance, and emergency readiness. The service vehicle becomes a visible commitment to reliability, signaling that the provider is prepared to bring skilled labor, technical expertise, and essential equipment directly to the location. This capacity strengthens trust between service providers and communities, enhancing accountability and expanding the reach of services that might otherwise be constrained by geography or logistical complexity. The result is a more resilient service ecosystem, where the vehicle itself is an instrument of continuity and a guarantee that work can be performed wherever it is needed, without excessive delays.

When we ask what the term service vehicle means, the answer is not a single definition but a consistent pattern across industries. It is the alignment of a vehicle’s design with a service mission, the inclusion of equipment and systems that support on-site work, and the capacity to reduce downtime and improve outcomes for customers and communities. A service vehicle is a practical assertion that mobility can be leveraged to deliver value in ways that pure transportation never could. This concept resonates with the broader trend toward mobile service delivery, where the boundary between workshop and field blurs, and where a well-equipped vehicle becomes the most reliable point of contact between service providers and those who rely on them. In grasping this, we begin to see that the value of service vehicles lies less in their appearance than in their capacity to enable swift, competent, and compliant work on site. The vehicle is, in a very real sense, the moving face of a service organization, representing its readiness, its capability, and its commitment to customers or the public.

For readers seeking further exploration of how these ideas translate into real-world practice, consider visiting the broader resource hub that discusses fleet-related concepts and service vehicle definitions. The hub provides context for understanding how these vehicles fit into everyday operations and long-term planning. kmzvehiclecenter blog (https://kmzvehiclecenter.com/blog/). This reference point helps connect the theory of mobile service platforms with the practical realities of maintenance schedules, safety considerations, and business strategy.

The overarching takeaway is simple and powerful: a service vehicle is defined by its function as a mobile service site, a conduit for on-site expertise, and a tool for delivering the public or client-facing duties that keep systems running and communities connected. It is the convergence of transportation, equipment, and human labor into a single, purpose-built unit designed to extend service capabilities beyond the confines of a workshop. The vehicle’s design—storage, mounting for tools, power sources, accessibility features, and safety provisions—says as much about the service organization as the technicians who use it. In that sense, understanding a service vehicle means recognizing how fleets are built not merely to transport but to enable, sustain, and accelerate service delivery in a world that increasingly relies on timely, on-site problem solving. This is why the phrase service vehicle carries practical weight across industries: it signals that the journey is not a prerequisite for service but the very channel through which service is delivered, sometimes even where the road ends and the work begins.

External perspectives offer additional depth on how scholars and practitioners articulate the concept. For a concise external reference on service vehicle definitions and their regulatory contours, see external resources that discuss the term in formal contexts. This external viewpoint complements the in-house and industry-specific descriptions, helping readers connect the practicalities of fleet design with the legal and economic frameworks that shape how service vehicles are used. https://www.lawinsider.com/dictionary/service-vehicle

Lifelines on Wheels: How Service Vehicles Mold Public Safety, Infrastructure, and Everyday Life

Service vehicles exist to deliver more than movement; they are platforms for services, networks, and resilience. They are designed to reach people where and when they need help, maintenance, or access to essential resources. While the phrase “service vehicle” may seem straightforward, it encompasses a spectrum of roles that keep societies functioning. In urban life, these vehicles are not mere conveyances; they are dynamic extensions of public systems, coordinating with dispatch centers, utility networks, and community needs to translate planning into practical, reliable outcomes. When we observe a city in motion, we are often watching service vehicles at work—arrivals on call, responses coordinated with other branches of government, and operations that quietly sustain daily routines.

Emergency response vehicles illustrate the core purpose of this class of machines. An ambulance does more than transport a patient; it carries life-saving equipment, supports rapid triage, and provides incident management in motion. Fire apparatus do not simply carry firefighters but shuttle critical tools, water, and communications gear to scenes where time and precision determine outcomes. Police vehicles function as portable command posts, aligning information from the field with situational awareness at a distance. The common thread across these units is a tightly choreographed balance of speed, safety, and information sharing. The efficiency of the entire public safety ecosystem depends on the reliability of these fleet operations: the readiness of the vehicle, the quality of the crew, and the clarity of the command structure that guides their deployment. Each crisis reveals how service vehicles, by serving as on-the-ground extensions of governance and emergency medicine, shape public trust as much as they shape outcomes.

Beyond emergency response, maintenance and repair fleets keep communities connected and functional. Tow trucks, road service vans, and mobile repair units do not exist solely to fix stranded vehicles; they act as the mobile arm of a broader infrastructure network. When roads need attention, service vehicles are dispatched to retrieve disabled assets, deliver spare parts, and perform on-site diagnostics that would otherwise require more time and cutting-edge facilities. The immediacy of roadside service reduces downtime for essential commerce and communication. In densely populated areas, a single fleet vehicle can avert cascading delays by ensuring that a malfunction does not paralyze adjacent services. The logic extends into fuel stations, data centers, and traffic management hubs where technicians travel with parts and maps to restore, recalibrate, and requalify. This on-demand capability is a practical expression of resilience in the face of a complex, interdependent system.

Utility and municipal fleets reveal another facet of service vehicles: their role in maintaining the public realm. Garbage trucks, street sweepers, and snowplows operate on predictable cycles, yet their impact on quality of life is measured in real time by cleanliness, safety, and mobility. Waste collection keeps cities sanitary and reduces public health risks; street cleaning preserves walkability and aesthetics, especially in commercial cores where foot traffic matters. Snowplows illustrate seasonal dependency, where a fleet’s readiness can determine whether a neighborhood maintains access to essential services during storms. These vehicles also symbolize a government’s capacity to plan for recurring conditions, translating budgets into predictable routines that residents come to rely on. When fleets perform well, communities experience smoother waste management, healthier streets, and reduced friction in daily life. When fleets lag, signs of strain appear in the form of litter, slick roads, or uneven access to facilities—visible indicators that investment, maintenance schedules, and asset replacement must keep pace with demand.

Mobile service units broaden the concept further by extending service delivery beyond fixed facilities. Mobile clinics bring health and preventive care to neighborhoods without requiring patients to travel long distances. Mobile banking vans, food vendors, and pop-up service centers expand access and economic participation, demonstrating the social value of a vehicle that is both a transport and a service platform. The underlying principle is simple: a well-positioned mobile unit can reduce barriers, democratize access, and adapt to shifting demographics. In practice, these units depend on careful logistics: scheduling, route planning, and real-time communication that ensure services reach the intended communities at the right times. The fleet’s flexibility becomes a public asset, capable of meeting evolving needs, whether for routine health checks in underserved areas or emergency relief in disaster zones.

The societal significance of service vehicles extends beyond immediate outcomes. Public confidence in government and municipal services often hinges on the visible competence of the fleet. A city that maintains its vehicles, adheres to modern safety standards, and updates equipment signals to residents that their needs are a priority. Conversely, aging fleets can erode trust, highlighting gaps in funding and governance. When citizens see fleets that appear neglected, questions arise about transparency, accountability, and the allocation of resources. This is not only about aesthetics or status; it is about predictable performance, safety, and the assurance that essential services will be available when demanded. In this sense, service vehicles function as material indicators of institutional capacity, and their presence or absence communicates a city’s commitment to resilience and inclusion.

Technology has begun to redefine what service vehicles can do, moving them from passive tools to proactive, data-driven partners. Connected vehicle systems enable real-time data exchange among vehicles, command centers, and field personnel. Dynamic routing leverages traffic conditions, incident reports, and resource availability to minimize response times and downtime. This intelligent coordination matters across the spectrum—from ambulances that reach patients faster to utility fleets that isolate outages quickly and dispatch repair teams with the right parts in hand. The health of a service fleet increasingly depends on software platforms that harmonize vehicle sensors, asset inventories, and maintenance calendars. Predictive maintenance, for example, helps fleets anticipate component wear before failures occur, reducing unscheduled downtime and extending vehicle lifespans. As fleets become more integrated, data becomes a strategic asset: it informs capital planning, prioritizes safety investments, and supports accountability through auditable performance metrics.

Electrification and sustainability further reshape the landscape of service fleets. Electric service vehicles reduce emissions and improve local air quality, addressing public health concerns in dense urban cores. The transition also brings new operational considerations: charging infrastructure, battery life under heavy duty use, and the need for rapid recharging at shift changes or in emergency dispatch windows. Fleet managers must balance range, weight, and duty cycle, ensuring that vehicles can complete back-to-back assignments without compromising safety or service levels. The environmental upside aligns with broader municipal goals to meet climate targets while maintaining reliability. Achieving this balance often requires smart procurement that blends electrification with resilience, such as strategic charging hubs and energy management that avoids peak demand times. In practice, the shift toward cleaner fleets conveys a message about responsible governance—one that prioritizes health, equity, and long-term affordability while preserving the essential functions service vehicles perform.

The human dimension remains central to the story of service vehicles. Fleet success depends not only on engineering and procurement but also on the people who operate, maintain, and manage these assets. Skilled drivers, technicians, dispatchers, and managers collaborate to keep services timely and safe. Regular maintenance, rigorous safety training, and clear protocols reduce risk and improve morale. Public perception of government efficiency is often shaped by the visible upkeep of these fleets—the cleanliness of vehicles, the quiet efficiency of maintenance work, and the absence of breakdowns in critical moments. Communities that benefit from well-functioning fleets also tend to experience a sense of security. Residents feel that their neighborhoods are cared for and that the institutions responsible for common goods are competent stewards of resources. The workforce dynamics involved reflect broader social currents: ongoing training to keep pace with technology, career paths that reward expertise, and a culture that values reliability as much as speed.

As cities grow more complex, the role of service vehicles in urban planning and resilience becomes more pronounced. Designers and policymakers increasingly consider how fleets integrate with public transit, emergency management, and digital services. Fleet data feeds into performance dashboards that help officials assess readiness, allocate funding, and identify gaps in service delivery. This feedback loop supports better decisions about where to invest in new facilities, where to deploy mobile units, and how to optimize routes for both efficiency and equity. The goal is not to chase a single metric but to cultivate a living system in which vehicles, people, and processes reinforce each other. When designed with this holistic view, service fleets contribute to safer streets, cleaner environments, and more inclusive access to essential services—even in times of stress, scarcity, or disruption.

Looking forward, the evolution of service vehicles will likely hinge on a combination of autonomy, data governance, and integrated networks. Autonomous service vehicles promise to extend reach and reduce human exposure in hazardous conditions. They could support routine tasks in maintenance and logistics, freeing skilled personnel for more complex work. Yet autonomy raises questions about safety, job transitions, and the resilience of operations under unpredictable events. The path forward will require careful policy design, robust testing, and transparent communication with communities about how these technologies affect service delivery and accountability. Alongside autonomy, the continued emphasis on resilience—redundant fleets, diversified supply chains for parts, and scalable service models—will help ensure that essential functions endure through crises. The practical takeaway is clear: service vehicles are not static tools but adaptable elements of a broader social and political contract. Their design, management, and deployment encode the values a city seeks to uphold—safety, accessibility, environmental responsibility, and trust.

For readers seeking a practical route into this domain, the way ahead is to connect policy ambitions with on-the-ground realities: how vehicles move people to care, how fleets stay ahead of breakdowns, and how communities experience the ordinary reliability that makes daily life predictable. And as we study the evolving interface between technology and service delivery, it is important to recognize the human stories behind every fleet decision—the technicians who keep machines fit, the dispatchers who orchestrate responses, and the residents who benefit from dependable, well-run services. This is where the concept of a service vehicle becomes most meaningful: not simply a machine but a conduit for public purpose, a catalyst for efficient infrastructure, and a tangible expression of a community’s capacity to provide for its members.

If you want to explore more about practical fleet practices and how they support daily service delivery, you can visit the KMZ Vehicle Center blog for additional insights and guidance. KMZ Vehicle Center blog. For readers who are curious about the broader technological shifts shaping connected and smart fleets, the literature on connected vehicle technologies offers a deeper theoretical and practical backdrop. A concise overview can be found here: Connected Vehicle – an overview | ScienceDirect Topics.

Final thoughts

In summary, service vehicles play an indispensable role in our daily lives, providing essential services that keep our communities functioning well. From emergency response to infrastructure maintenance, these vehicles ensure the safety and efficiency of urban living. By understanding what service vehicles mean and their diverse types, local car owners, business operators, and everyday citizens can appreciate their value and necessity in contemporary society. Recognizing the importance of these vehicles can also encourage better support for the infrastructure and services they provide.